A Brief Historiography of OOP

To trace a history of object-oriented programming we have to travel back in time - the year: 1962, the land: Norway. A language called ALGOL is all the rage as people begin exploring ways of programming away from the bare metal. ALGOL is quite a feat given the technology of the time. Kristen Nygaard and Ole-Johan Dahl decided to build a little thing on top of ALGOL they dub Simula. The first version of this language was designed for discrete event simulation with the later Simula 67 introducing objects and classes. Now it’s interesting that OO begins here - so let’s pause and examine this more.

Discrete event modeling is a way of modeling systems that decomposes them into entities and events. We can already see the primordial shapes of OO within this context but it took Simula to accentuate and really bring them out in the way we’re all familiar with now - objects, classes, inheritance, virtual methods, and interestingly coroutines. Now it’s interesting that co-routines were included and given the context - discrete event modeling - we can see just how they’d be useful. The word object was at the time taken much more literally to correspond with a really existing object - Ship, Missile, etc. In such situations the entities do not represent a single straight-line of execution, but can interact with each other, just like real entities, in all sorts of interesting ways. With objects the idea is to isolate these entities and their logic. Co-routines were then one way of modeling the interdependencies between these objects. Between objects and coroutines we can see something like a primordial version of the actor model appear. This would be developed a few years later taking heavy inspiration from Simula.

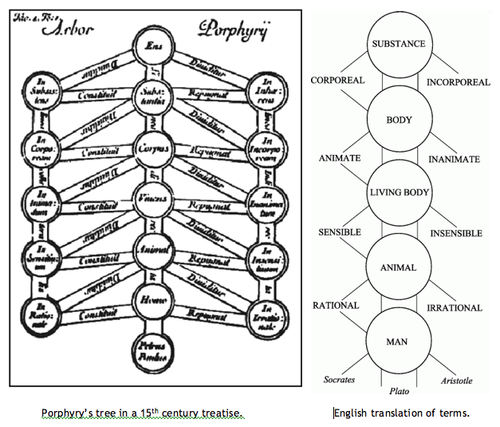

It is with Smalltalk that an interesting duality begins to emerge around the word object. The object in object-oriented programming can be taken in a double sense. Extrinsically, an object is a structure within the software that corresponds to a really existing entity or set of entities within the physical system being modeled - eg. Teller, Ship, Missile. Intrinsically, an object is a way of modeling parts of a program by dividing it up into genus-species hierarchies in an Aristotelian genus-differentia style (eg. App, File, Controller). Originally both senses seem to have been at play, and are often muddled together. Later on, however, we see the intrinsic definition of object begin to dominate. Objects are taken up as a means to modularize code that supplements naked functions (in languages where these are available) and modules. They are frequently treated as an intermediate level of modularization, though this approach takes a long time to work out.

Smalltalk eventually gives rise to the languages we are familiar with today C++ and Java. These languages are the first to achieve wide-spread success and to heavily spread the intrinsic view of object-oriented programming. It’s interesting to take a look at the OOPSLA proceedings. Firstly we see that functional languages have always been present but at the fringes. Smalltalk is the clear leader early on with some penetration by C++. By 1997, however, we see that Java has truly exploded onto the scene. This rise in object-oriented languages and particularly in languages with the intrinsic view of object-oriented programming seems well timed with the migration of machines outside specialized university and military facilities and into the lives of a wider segment of the population.

In the literature we also begin to see signs of wrestling with the intrinsic view of object-oriented programming. Writing software this way provides several layers of difficulty. Firstly, any two entities can be correlated and differentiated in an infinite number of ways. For example, my coffee cup and a pile of ash are related in that they’re both inanimate or both not purple. They differ in that I drink out of a cup but not out of a pile of ash. Secondly, this explosion of possibilities is usually resolved by falling back on preexisting biases or prejudices about the entities involved (eg. putting only two sexes or using sex instead of gender, etc). This puts software directly in contact with the material and social conditions of its creation. Systems and features begin to reflect the social relations underlying their construction. They also inherit the contradictions within organizations. Contradictions that had typically gone without formalization or enunciation. Power structures and political games within organizations begin to emerge as contradictions within their software. This gives software an organization-wide importance. The power structures that underlie organizations are codified and formalized and therefore made visible, at least somewhat, to programmers. As an interesting aside this would also mean that issues within the software departments of a business provide a good sympotomatic for the health of the organization they sit within. The software department may even give the first signs of increasing or decreasing dysfunction within organizations. Low quality software or frequent downtime, for example, can be seen as a symptom of dysfunctional leadership more than, as typically diagnosed, a software process failure.

As software migrates into the labor force aided by object-oriented programming the traditional, industrial era, power struggles begin to reappear. Firstly, object-oriented programming gives the illusion that software, if definitively decomposed at the beginning of a project, can be subject to estimation and rote mechanical creation since the components are already modeled. Businesses thus seize on object-oriented programming as a way to turn intellectual products into assembly-line constructions. Software, however, uniquely frustrates this endeavor. As the size of software grows the failures of this approach begin to pile up. Software consultants become frustrated by their inability to succeed. The mismatch between traditional construction with its upfront, top-down, piecework style and the realities of software come to a head. The end result of these and other similar struggles with the tensions of developing software within businesses express themselves in the agile methodologies. These documents attempt to find a new way, outside of software and within the business itself, to deal with the process of developing software. They attempt change by addressing dysfunction at the organizational level, and they often suggest collaboration across the entire organization. These practices are so difficult to introduce into existing businesses that an entire consultancy arises fundamentally about helping organizations remedy their internal dysfunction enough to develop software.

Summary and Conclusion

This post was born out of an experiment to see if anything interesting and novel could be discovered simply by tracing the history of object-oriented programming. We’ve only taken a brief and incredibly provisional look. What began as a historical outline shifted after a double-sense was found in the meanings assigned to the word object. The intrinsic definition ultimately wins out as it alone holds the promise of automating software development and making large software projects more understandable to the layman by using classical representative, hierarchical models of abstraction. This and similar advancements on the hardware and OS side lead to an explosion in the presence of computers within organizations. As software becomes more fundamental to organizations it comes to embody major aspects of the material conditions of these businesses as they must be codified in order to be converted into software. This puts software in contact with the material and social tensions of organizations and societies. This contact has the byproduct of allowing the quality of software to serve as a measure of dysfunction within an organization. Software is particularly sensitive to the internal contradictions and dysfunctions within businesses. If an organization cannot develop stable software then it must be incredibly disorganized internally. As this sensitivity is recognized and code bases continue growing in size there is a consonant emergence of software consultancies to develop RAD tools as well as diagnose and prescribe organizational fixes.

I basically stopped when it appeared the article could continue growing forever. What would naturally follow is a history of the failures/successes of RAD tools and the progression towards modern software development techniques. In order to get a clearer picture of these progressions and perhaps a better understanding a more in-depth view of the discussions within software communities about their perceived difficulties is needed. In addition there is much overlap between software and philosophy as regards appropriate systems for organizing encounters with the material and social world. These and more could provide fruitful directions for future software historiographies.